At this year's Pacific Northwest Section-American Water Works Association Conference—the Northwest's largest conference and trade…

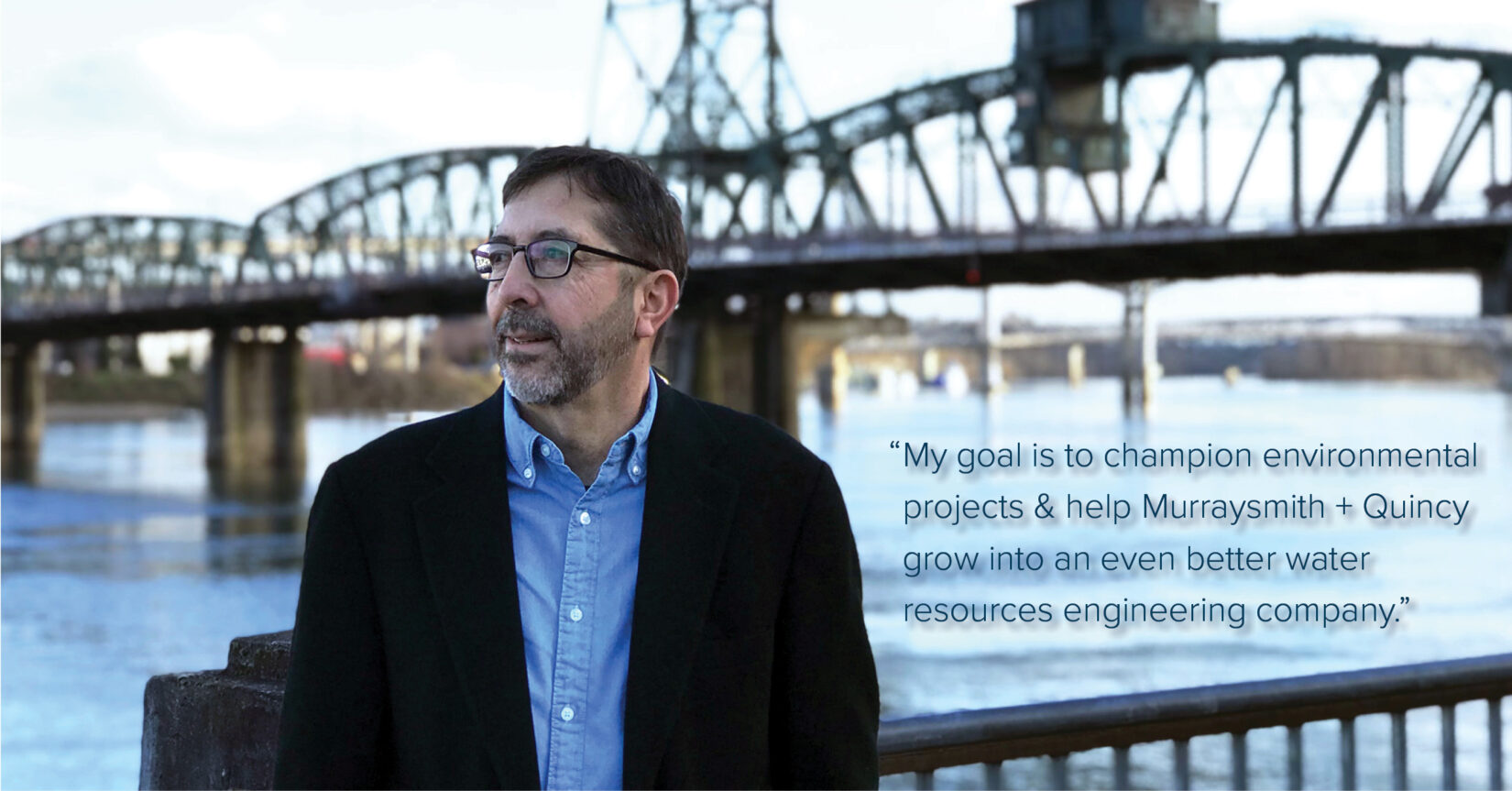

Portland Environmental Engineering and Water Resources Expert, Ken Vigil, Joins Murraysmith + Quincy

Ken Vigil, a Portland leader in the environmental engineering and water resources industry and former co-owner of the trusted firm Vigil-Agrimis, recently joined Murraysmith + Quincy. Ken is a well-respected expert in hydrology and hydraulics, stream and floodplain restoration, drainage design, stormwater and wastewater system planning and design, and water quality modeling.

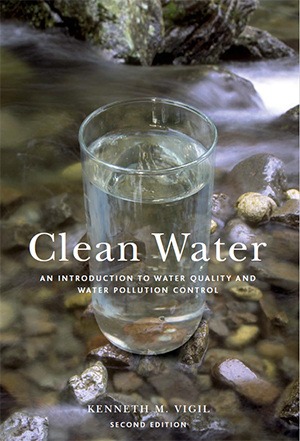

Ken has managed hundreds of successful projects and has won awards from the American Public Works Association, American Council of Engineering Companies, US Small Business Administration, State of Oregon, and others. He was the water resources engineer of record for the final design of Portland’s high-profile Tilikum Crossing Bridge over the Willamette River, with responsibility for hydraulic scour design, stormwater management, erosion control design, and fish passage. Ken is also a published author; his book—Clean Water: An Introduction to Water Quality and Water Pollution Control — is published by Oregon State University Press.

After enjoying a well-deserved reprieve following the successful sale and transition of his consulting firm, Ken is returning to the industry with energy and excitement to share his expertise and help Murraysmith + Quincy grow our work in stormwater and water resources engineering. We caught up with Ken last week to learn more about his background, his near-term goals, his decision to join the team, and what his focus will be at the firm:

What initially drew you to environmental engineering and water resources?

I’ve always loved the outdoors. I grew up in Ogden, Utah, fishing with my dad and participating in outdoor activities.

In college, I found out I had an aptitude for math. I wanted to figure out how I could put my love of the outdoors and my skills in math together. Civil engineers spend a lot of time outdoors, I thought, and certainly, they need to be good with numbers.

I have always had a strong environmental ethic. I graduated in 1977 from high school and the Clean Water Act was passed in 1972, so I was aware of water pollution as a key environmental issue.

At Utah State where I went to college, civil engineering was combined with environmental engineering. To me, environmental engineering was a natural fit because I loved the outdoors and water so much, and it hurt me to see water pollution occurring. I thought that I could someday use my skills to help prevent water pollution or help restore areas that had been damaged.

It’s interesting now, as I move toward the end of my career, I like the civil engineering part more and more because of how it can help communities. Transportation, for example, is so important in terms of equality—if people have equal transportation options, they can travel, they can get to work, and so forth. It does a lot for humankind, the various things that civil engineers provide.

What is your definition of sustainability and how does this definition inform your work?

It’s a tougher question than it would first appear on the surface. Sustainability is defined in various ways. The word sustainability comes from “sustenance.” For me, it’s practices that promote well-being for the planet and humanity—practices that can be repeated and allow us to maintain that well-being.

One of the coolest ways that I’ve experienced sustainability in civil engineering was when a client had us do a deconstruction demo plan for a building which had old Doug fir timber. Here we were with our civil engineering hats, trying to determine not how to build a building, but how to de-engineer it to preserve the materials.

What is one of the most important lessons you’ve learned in your career thus far?

When I’m considering lessons learned, I often think about what I try to teach young professionals. One thing I always say to them is that no matter what, do good work. Clients and peers will remember when you provide a high-quality product. In fact, this is the reason I was able to start my own company. I used to work for DEQ and, when I left to start my own company, one of the people I had worked with at DEQ had just gone to work for Port of Portland. Because this person knew I did great work, he hired me, and the Port ended up becoming one of our biggest clients.

Another lesson is to always be a good listener, no matter what level you work at. You can perform so much better if you listen to what your clients say they want. Rather than jumping in with a different point of view, stop and take the time to really listen. Perhaps you will end up sharing the same point of view, or realize they had an even better idea than you did.

Lastly, this kind of work is really challenging. There are deadlines. Things get heated because of a technical issue, maybe money. I feel strongly that an important lesson is treating others with kindness. It doesn’t take anything to be kind and you can be so much more productive when you are. When you know things are going to be difficult, that’s the time when you need to show more kindness.

Where do you think stormwater is headed in the next ten years? Is stormwater as important now as it was 20 years ago?

If you start at the largest scale, we’re looking at watersheds. We can manage erosion and keep vegetation near the stream corridors for filtration and shade. If we must use chemicals, we can use those that will biodegrade easily and won’t stay in the environment. From there you move to the roadway scale, collecting and running stormwater through natural treatment facilities. At the site scale, we’re doing amazing things with urban stormwater through programs like LEED. We have also made progress looking at the biological effects of stormwater, particularly how metals like zinc and copper are impacting salmonids even in smaller quantities than we originally realized. There are things we can do, like selecting different types of paint or looking for ways to de-ice roads without using salts.

When we work to make improvements in the environment, we identify a need, we address that need, and while you never can do it a hundred percent, you make progress. At some point, people have an awareness of another need and they shift focus towards that. That’s natural and important. Right now, anyone who is doing civil engineering needs to pay attention to climate change. Thankfully, a lot of these things work together. When we protect our green spaces it provides a good place to treat stormwater run-off, it takes out some of the carbon dioxide in the air, and it helps cool concrete heat sinks—instead of the sun shining on a big building, parks can absorb some of that solar radiation.

For civil engineers, we need to get smart and develop skillsets that will help address climate change. Sometimes, we already have the tools, we just need to learn to apply them in the right way.

How do you plan to help Murraysmith + Quincy leverage its existing tools and resources to help solve big issues like climate change and water pollution?

Murraysmith has always been regarded as a solid civil engineering firm, and it’s exciting to see it develop stronger services for stormwater, natural systems, and water resources. When you’re in the water business, wetlands are hugely important. If you can restore wetlands, it’s good for the fish, it’s good for stormwater, it’s good for temperature. I hope that by coming to Murraysmith + Quincy, I can bring some of my skillset to help encourage staff to bring more of this kind of work in-house, leveraging existing skills and interest in staff at the firm. My goal is to champion environmental projects and help the firm grow into an even better water resources engineering company through my involvement. One of the reasons I joined the firm was that I wanted to find a place that really valued my strong water resources background. It is satisfying to share my experience and help make connections.

You’ve led a robust professional career including building an award-winning water resources and environmental firm, which served a wide range of public agencies around the Pacific Northwest. After enjoying a well-deserved break following the sale and transition of your former consulting firm, why are you returning to the industry now?

I started looking in the rearview mirror, and I realized there were still some things I could have or would have liked to do in civil engineering. I like the team aspects of engineering work, working with like-minded people doing things for the community, whether it’s a road or a sewage treatment plant.

Ultimately, I decided I still had a lot to offer. I don’t know if our clients are going to move quickly enough into climate change mitigation for me to participate, but I hope so. A lot of the issues in climate change right now have to do with water—the hydrology is changing. Another thing I have really enjoyed about my career is the mentoring I have done. There are some strong engineers out there who I helped mentor—I hope that by getting back into this work I have the opportunity to mentor more young engineers.

After talking with Kyle McTeague, who I came to respect and enjoyed working with through our collaboration on Kane Drive, the pieces of the puzzle started to come together. I realized the potential to help Murraysmith + Quincy grow their water resources group. I knew I needed to find the right fit. What I wanted was something that could provide a benefit to the organization I’m working for, our clients, me and my family, our community, and the planet.